Mt Shasta: The Lonely Mountain

19 April 2015

A quake went down my spine as I gazed for the first time upon the bulk of Mt Shasta. This is a very large mountain. The familiar thought fired through my dizzied mind, ‘Can I really do this?’ to which I responded, in that odd self-contained dialogue familiar to the solo climber, ‘I don’t know and I don’t care but I’ll be damned if I don’t give it a shot.’

I packed up the trail from Bunny Flat at 10:00 on a Saturday morning, headed for Horse Camp and the base of Casaval Ridge. Fully equipped with waterproof gaiters and shell pants, plastic mountaineering boots, and ice axe and ice tool I must have actually looked like a respectable mountaineer. More importantly I felt strong, from training for a half Ironman triathlon for the past few months, and confident in my systems, which I had tested just two weeks before on a successful climb of the East Couloir on Matterhorn Peak. Now I found myself on a true mountain’s mountain at the start of a long journey there and back again.

The whole sweeping arc of Shasta humbles anyone moving through it. Pine forests rise thousands of feet from not just the valley floor but above all terrain visible for miles and miles clear to the horizon. The quiet calm of the forests puts me at ease and washes away all the trepidation and anxiety I felt at the trailhead. Before I know it and after simply following a northern heading I stumble across a ranger near Horse Camp. He most courteously points me toward a folder laying on the ground that contains details of current climbing conditions organized by route on the mountain. I read aloud ‘Casaval Ridge is in excellent condition…,’ and exclaim ‘Yes!’ and we share a laugh. I pass through the camp where Search and Rescue personnel have gathered along with the first of many of the guided groups I would see on the mountain, this one going for a ski tour on the western slopes.

Now the terrain steepens and I employ what I have since learned is called the ‘French technique’ of climbing with crampons. I make the elevation gain easy by taking long moderate switchbacks back and forth past others’ tracks, some of which follow the slope straight upward. I have plenty of time today to get to camp on the ridge at just under 10,000 ft. A mere three hours after departing the trailhead I crest the toe of the ridge and traipse into camp. I suddenly realize there are a lot of people on this mountain. I talk with skiers and climbers of all abilities, ambitions, and backgrounds in a manner reminiscent of that on the Whitney Trail. Many of the people on the mountain seem to have been drawn solely to Shasta with few other hiking experiences to speak of. I unpack my shovel and dig one hell of a bivy shelter, which I dub the ‘bivy coffin.’ The shelter has a place to sit and a cooking shelf. But I later discover it lacks proper ventilation as cool air sweeps over the slope and settles between the confined walls. I learn a valuable lesson on the importance of constructing an opening lower than sleep level to prevent cool air and undue moisture from settling in the shelter.

As the sun goes down I jaunt up the broad slope to the west of camp leading to the ridge proper. The reconaissance later provides high utility while route-finding under a moonless, clear starry sky. I make plans to set out with a large party at 3:30 the following morning to maximize travel distance through good snow conditions. The party consists of relatively inexperienced climbers, but they are a prepared and enthusiastic bunch nonetheless: the leader and the father of two young boys, who are on the climb along with one of their friends, and another middle-aged gentleman who must be a friend of the family or perhaps a work acquaintance of the trip leader. It is always interesting to see what I share in common with strange folk and as it happens the middle-aged gentleman is an electrical engineer with CALTRANS. I was assigned to electrical inspection detail during one of my summers spent on construction of the I-94 Mitchell Interchange back in good old Milwaukee. We get to talking about all the intricacies of delivering a successful project from plan to enforcing specifications to final constructions.

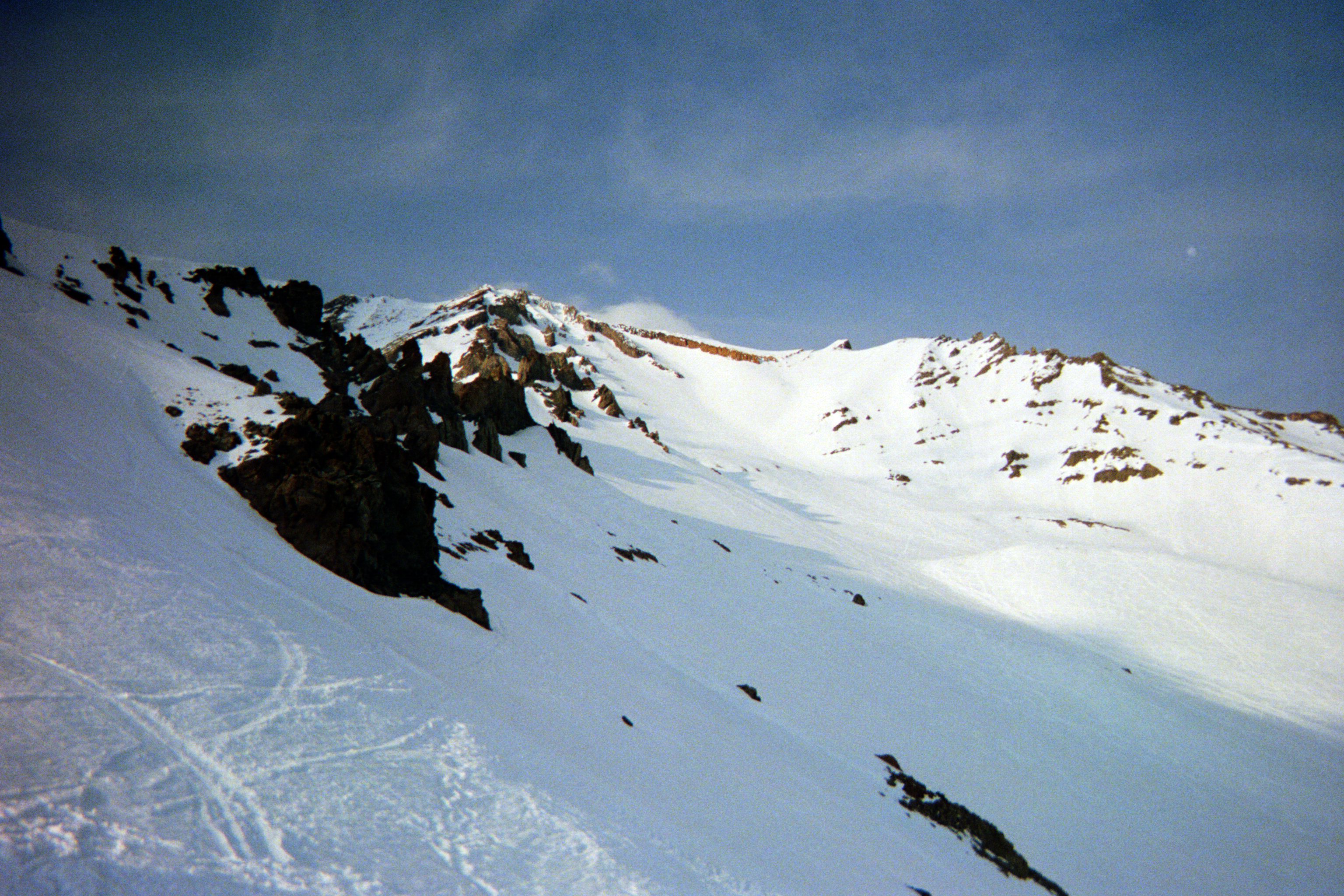

Now I suspect no one really gives a shit about all these mundane details so here’s the good stuff. Being the strongest climber I led the group up the ridge with some suggestions from the trip leader of course. We were very fortunate to be able to follow a path forged by a guided group that had a hard time of it the previous day. They apparently postholed their way to just below the catwalk before turning around due to time constraints and lack of confidence of one of their party members. I exclaimed, ‘It feels like cheating!’ as I placed my foot carefully into the same point they had such a short time ago. I expect we encountered much more favorable conditions because it was good and cold this night, certainly below freezing. At some points along the traverse I was able to walk forward, simply planting the spike of my axe vertically into the slope for balance, while at other times I was only comfortable facing the slope, sliding my feet across as an accordion, swinging the picks of axe and tool into the hardened western aspect. I was glad to see only a small cone illuminated by my headlamp as I got the sense the slope dropped off sharply beneath the traverse.

All of a sudden the traverse ended and I jogged up onto the crest of the ridge, gratefully resting and removing my pack atop a perfectly placed sitting rock. The first light of dawn already shone in the east. I took a good and long break and ate breakfast to replenish my reserves for the long climb to come, allowing the party to proceed ahead. The leader pointed out a nice line across a more moderate traverse on lower angle slopes toward a steep exit back onto the crest. I ended up in front again and relished the steep exit. ‘Hyaah hyaah!’ I yelled triumphantly. I felt sublimely comfortable with a tool in each hand. The ice tool in particular plunged remarkably easily and securely into the crusty surface.

Where my legs had felt sluggish during the earliest efforts of the day, they now felt warm and powerful. Like they did not belong to feeble me. I waited a short time for the party to make the steep exit, and we headed across more flattish terrain. I had seen terrain like this before and knew to stay low as the slope wrapped around into a wide gully. The party seemed intent on staying high, was forced to make an awkward descending traverse, and I once again found myself in the front. I now recognized the small ‘wineglass’ apron described to me yesterday by the trip leader and aimed just to the right of it, where there appeared to be another rest spot beneath the crest. The party really began to get strung out during this second steep section. My engineering friend was doing really well, arriving at the rest spot with me. I said, ‘I’m feeling good; I’m going to go check out the wineglass,’ since it looked difficult to surmount. ‘You can do that,’ he suggested heartily, ‘Because you have young legs!’ We shared a laugh and I waved back from atop the wineglass, which turned out to be very manageable. This would be my final contact with the party, an unceremonious goodbye to people I had grown close to in a very short time, but a necessary one. I wanted to take full advantage of the sunny, wind-less conditions currently holding at high altitude on this tempestuous mountain. I certainly hope the party made it to the summit. I’ll bet they made it!

Well now my thoughts turned toward finding the famous catwalk. I scanned the crest of the ridge for a wall of reddish volcanic rock and saw one, yet there were no tracks leading to it; furthermore the slope beneath the wall appeared to be dangerously corniced. I imagined myself plunging right through the damned slope. ‘No that can’t be it,’ I thought to myself, ‘It must be ahead.’ So I moved upward, keeping a short distance below the ridge, always on the west side, until I joined a few different climbers who had in fact climbed the entirety of the western slopes. ‘Are you guys planning to walk across the catwalk?’ I asked. ‘I’m pretty sure it’s down there, man,’ one of them replied. ‘Aw damnit!’ I relent. And surely it was, and maybe it was even the wall I had seen earlier, because we trudged up the final section of the western slopes to a staggering view of the Misery Hill cone and the very summit of Shasta itself. I was mildly upset to have missed the catwalk, but acknowledged that it would not have been a safe route for me to take, climbing alone and without any real knowledge of this section purported to have tremendous exposure.

Now I began to feel the altitude and the meaning of Misery Hill. However it was over soon enough. I joined a veritable conga line of climbers ascending from the Avalanche Gulch route. There must have been over a hundred climbers on the route. It was silly. I had never seen that many climbers on a mountain before, and it was quite unsettling after ascending the mostly deserted ridge. Now everyone was making their way around the backside of the final summit cone on more moderate snow slopes when I spotted a steep little chute that looked to provide ‘mixed climbing.’ I held up my tools in my hands and went for it! ‘Wow this is great! What a surprise!’ I exclaimed in my head. I was expecting a boring slog to the summit. I made a mistake and ran into some airy, crumbly snow and ice near the top and had to downclimb over to the right side of the chute. I noticed some people were watching me from the summit and tried to look like a pro. And there it ended. I swung the axe one last time and found myself standing beside the register. I congratulated a few of the people I had seen either near the trailhead, at camp on the ridge, or on the summit plateau, and took a phenomenal picture (accidentally) with a Russian expedition on the very high point.

I have said it before and will say it again, because I felt it again, this time more acutely, that coming back down was not only my final literal objective but an emotional challenge as well. To willingly embark on a journey, to overcome such great heights and feel the warm embrace of the mountain only to return to bitter ordinary reality; hurts.

I started to hurt physically as well as emotionally as I was overcome with a mild altitude headache on the descent, which proceeded rapidly, thankfully. I would like to point out that a mild altitude headache feels like getting hit by maybe a small bus or van instead of a freight train, which of course represents full blown mountain sickness in this unfortunate analogy. I had pushed the boundaries of weekend warring to new heights (combined with bookend 10 hour drives from and to Ventura) and was paying the price for lack of acclimatization time. The descent from hell continued ever onward as I was unable to get much good glissading accomplished. There were too many ball-crushing bumpy footprints all up and down the gulch, and the untouched sections remained icy as it was still just midday. At the very least I (deliberately) practiced some highly realistic self-arrests after out of control falls from various stances. I was then presented with the challenge of regaining the ridge and my campsite. Not wanting to gain elevation I desperately traversed across ever-loosening slopes which seemed to be facing directly into the sun. And what a sun it was, beating mercilessly down on me, turning the gulch into a sarlacc oven of despair. I finally completed the slippery traverse and laid down to nap for a short time to regain my senses. I unexpectedly got my second wind and my headache vanished. I frolicked down the lower slopes by an effortless blissful jog-slide movement and looked back upon Shasta with a warmed heart.