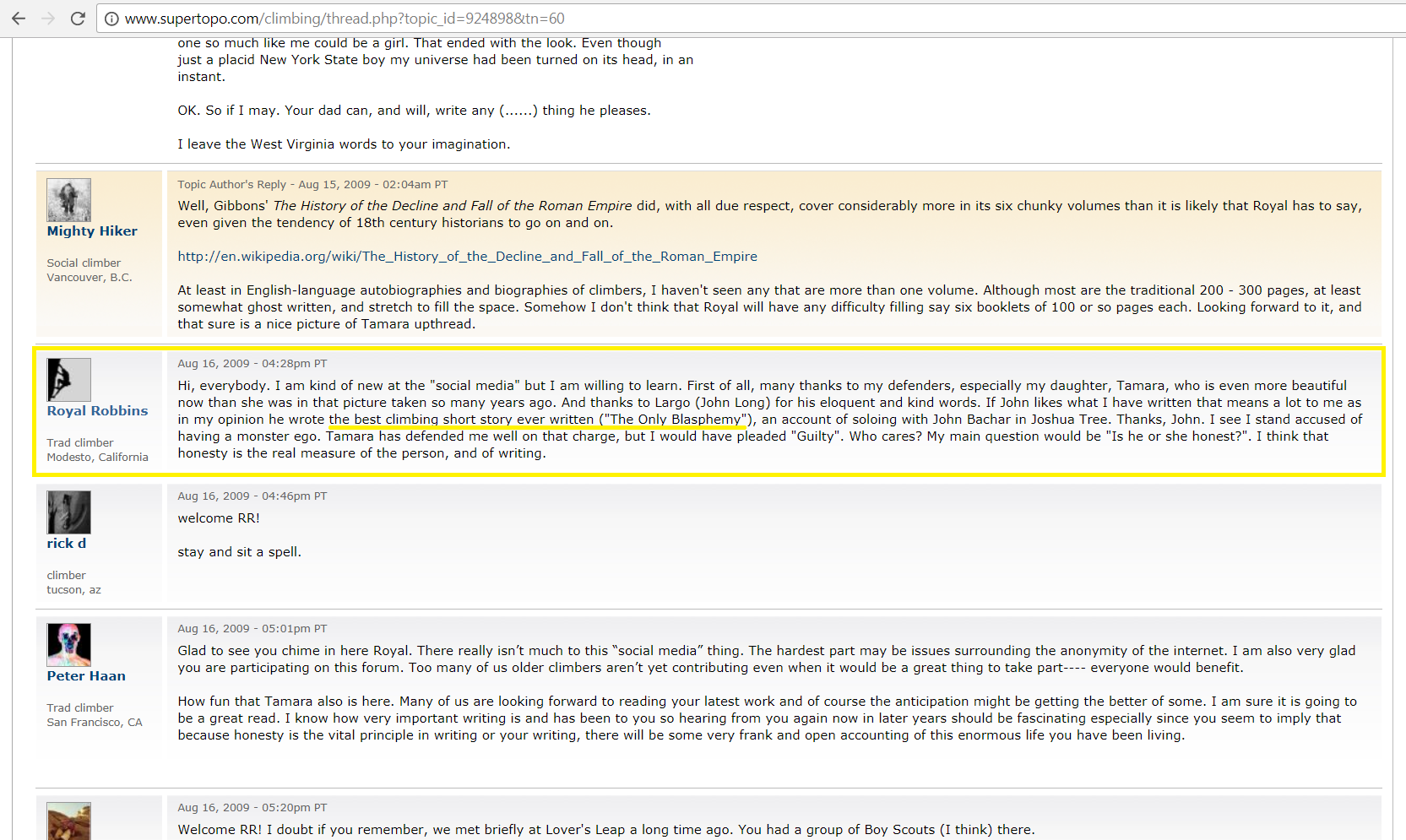

Here’s a rare Supertopo post from climbing legend, Royal Robbins:

And the short story from John Long:

You could spend a lifetime absorbing the rich history of climbing…hell you could spend a lifetime digging into the Supertopo forums!

In case the above link breaks at some point in the future, John Long’s story herewith shamelessly copied:

At speeds beyond eighty miles an hour the California cops jail you, so I keep it down in the seventies. Tobin used to drive one hundred, till his Datsun exploded in flames on the freeway out by Running Springs. Tobin was a supreme artist, alive in a way the rest of us were not. But time seemed too short for Tobin, who always lived and climbed like he had days or perhaps minutes before the curtain fell. It came as no surprise when he perished attempting to solo the north face of Mount Alberta—in winter.

I charge on toward Joshua Tree National Monument, where two weeks before, another pal had “decked” while soloing. I inspected the base of the route, wincing at the grisly blood stains, the tufts of matted hair. Soloing is unforgiving, but okay, I think. You just had to be realistic, and can never stove to peer pressure or ego. Soul climbing, and all that jazz. At eighty-five miles an hour, Joshua Tree comes quickly, but the stark night drags.

The morning sun peered over the flat horizon, gilding the rocks spotting the desert carpet. The biggest stones are little more than one hundred fifty feet high. Right after breakfast I run into John Bachar, widely considered the world’s foremost free climber. For several years he’s traveled widely, mostly in his old VW van, chasing the sun and the hardest routes on the planet.

Most all climbs are easy for Bachar. He has to make his own difficulties, and usually does so by doing away with the rope. He dominates the cliff with his grace and confidence, never gets rattled, never thrashes, and you know that if he ever gets killed climbing, it will be a gross transgression of all taste and you’ll curse God for the rest of your life—on aesthetic, not moral grounds.

Bachar has been out at Joshua Tree for several months and his soloing feats astonish everyone.

It is wintertime, when college checks my climbing to weekends, so my motivation is there but my fitness is not. Straightaway, Bachar suggests a “Half Dome day.” Yosemite’s Half Dome is two thousand feet high, call it twenty rope lengths. So we’ll have to climb twenty pitches, or twenty climbs, to put in our Half Dome day.

Bachar laces up his boots and cinches the sling on his chalk bag. “Ready?” Only then do I realize he means to climb all two thousand feet solo, without a rope. To save face, I agree, thinking: Well, if he suggests something too crazy, I’ll just draw the line. I was the first to start soloing out at Josh anyhow.

We cast off on vertical rock, twisting feet and jamming hands into bulging cracks; smearing the toes of our skin-tight boots onto tenuous warts and wrinkles; muscling over roofs on bulbous holds; palming off rough rock and marveling at it all. A curious little voice occasionally asks me how good a flexing, quarter-inch hold could be. If you’re solid, you set curled fingers or pointed toes on that quarter-incher and push or pull perfunctorily. And I’m solid.

After three hours we’ve disposed of a dozen pitches and felt invincible. We up the ante to stiff 5.10, the threshold of expert terrain. We slow, but by early afternoon, we’ve climbed twenty pitches: the Half Dome day is history. As a finale, Bachar suggested we solo a 5.11—an exacting drill even for Bachar, for back then the 5.11 grade moves us within a single notch of the technical limit. I was already hosed from racing up twenty different climbs in a few hours, having cruised the last half dozen on rhythm and momentum. Regardless, I follow Bachar over to Intersection Rock, the communal hang for local climbers and the site for Bachar’s final solo.

Bachar wastes no words and no time. Scores of milling climbers freeze when he starts up, climbing with flawless precision, plugging his fingers into shallow pockets in the 105-degree wall, one move flowing into the next much as pieces of a puzzle match-fit together. I scrutinize his moves, making mental notes on the intricate sequence. After thirty feet he pauses, directly beneath the crux bulge. Splaying his left foot out onto a slanting edge, he pinches a tiny flute and pulls through to a giant bucket hold. Then he hikes the last hundred feet of vertical rock like it’s a staircase. A few seconds later he peers over the lip and flashes that sly, candid snicker, awaiting my reply.

I am booted up and covered in chalk, facing a notorious climb which just now (1974) is rarely done, even with a rope. Fifty hungry eyes give me the once over, as if to say, “Well?” That little voice says, “No problem,” and I believe it. I draw several deep breaths. I don’t consider the consequences, only the moves. I start up.

A body-length of easy stuff, then those pockets, which I finger adroitly before pulling hard. This first bit passes quickly. Everything is clicking along, severe but steady, and I glide into bone-crushing altitude before I can reckon. Then, as I splay my foot out onto the slanting edge, the chilling realization comes that, in my haste, I’ve bungled the sequence, that my hands are crossed up and too low on that tiny flute that I’m pinching with waning power.

My foot starts vibrating and I’m instantly desperate, wondering if and when my body will freeze and plummet. I can’t possibly down climb a single move. My only escape is straight up. I glance down beneath my legs. My gut churns at the thought of a freefall onto the boulders, of climbers later cringing at the red stains and tufts of hair. They look up and say, “Yeah, he popped–from way up there.” A montage of black images floods my brain.

That little voice is bellowing, “Do something! Fast!”

My breathing is frenzied while my arms, gassed from the previous two thousand feet of climbing, feel like concrete. Pinching that little flute, I suck my feet up so as to extend my arm and jam my hand into the bottoming crack above. But I’m set up too low on that flute and the only part of the crack I can reach is too shallow, accepts but a third of my hand. I’m stuck, terrified, my whole life focused down to a single move.

Shamefully, I understand the only blasphemy—to willfully jeopardize my own life, which I have done, and it sickens me.

Then everything slows, as though preservation instincts have kicked my mind into hyper gear. In a heartbeat I’ve realized my desire to live, not die. But my regrets cannot alter my situation: arms shot, legs wobbling, head on fire. Then fear burns itself up, leaving me hollow and mortified. To concede, to quit, would be easy. The little voice calmly says: “At least go out trying.” I hear that, and punch my hand deeper into the bottoming crack.

If only I can execute this one unlikely move, I’ll get an incut jug and can rest on it, jungle gym style, before the final push to the top. I’m afraid to eyeball my crimped hand, scarcely jammed in the bottoming crack. It must hold my 205 pounds, on an overhanging wall, with scant footholds, and this seems ludicrous, impossible. My body has jittered here for close to a minute. Forever.

My jammed hand says “No way!” But that little voice says, “Might as well try it.”

I pull up slowly—my left foot still pasted to that sloping edge—and that big bucket hold is right there. I almost have it. I do. Simultaneously my right hand rips from the crack and my weight shock-loads onto my enfeebled left arm. Adrenaline powers me atop the “Thank God” bucket where I try and suck my chest to the wall and get my weight over my feet. But it’s too steep to cop a meaningful rest so I push on, shaking horribly, dancing black dots flecking my vision, glad only that the terrain, though vertical, is casual compared to below. Still, it takes an age to claw up the last hundred feet and onto the summit.

“Looked a little shaky,” laughed Bachar, flashing that candid snicker. I wanted to slap it right off his face.

That night I drove into town and got a bottle. The next day, while Bachar went for an El Cap day (three thousand feet, solo, of course), I wandered through dark desert corridors, scouting for turtles, making garlands from wildflowers, staring up at the titanic sky—doing all those things a person does on borrowed time.