Devils Crags

23 June 2018

From the pangs of fear and freedom writ large on backwoods mountain ridgelines — this should be pretty easy for any climber to understand.

Garrett’s infectious enthusiasm for climbing all the big peaks as soon as possible had got to me. Our motors were revving high for the trip to Devils Crags. It became our rallying cry and anyone we met on the trail unfortunate to ask what we were doing with a rope on the JMT – well, they immediately got our instinctual response, ‘We’re climbing Devils Crags!!!!’ The slightest provocation could set us off on tales of old hard men climbing knife edge ridgelines and chossy chimneys, the like of which could be found in quantity on the Crags.

‘Wow never heard of it, good luck and be safe guys.’ The typical hiker response. The very same hikers that in the words of one trip report author, ‘couldn’t name a single peak between Whitney and Half Dome.’ Classic!

The approach to camp was fairly uneventful. It would take a few more miles on the return journey before my hips started to collapse under the weight of our 70 meter rope.

[Hint: a 40 meter rope will do you just fine on this climb. Only problem was, neither of us could stomach chopping up a perfectly good workhorse / cragging rope into little alpine bits.]

With the long summer solstice just a day behind us, the Crags were illuminated with the brilliant alpenglow of days gone by as we ramshackled our way up Rambaud Creek. As others have noted, stay high above the creek on its north side to avoid the brush. You’ll endure some sidehilling, but we found that pointing ourselves toward groves of trees helped to avoid the plagues of manzanita.

We crossed Rambaud Creek twice, first to its south side somewhere around 10,000’ and then back to its north side somewhere around 10,400’ in order to avoid a horrid looking talus slope north of the creek between these elevations. It was worth it until Garrett soaked his foot on the second crossing. We were busted up from carrying the packs all day and so made our camp at the very first little pond at 10,400’.

I would like to say I slept good that night, content with our preparations for the climb. However, I tossed and turned all night. Garrett’s odd breathing patterns didn’t help but one can hardly blame a tentmate for a little snorting here and there. Nonetheless we were up with the sun, brewing coffee and generally breaking camp in as slow a fashion as possible.

As we made for the higher lakes, Garrett realized he had forgotten his harness. Being such an understanding partner, I offered to scout the path ahead while he went back to grab it, ‘You’ll catch up with me anyway man.’ Such selflessness, I mean I could have gone back with him, but at that point my momentum was too much to change directions.

We regrouped on a flat rock below Rambaud Pass. The way ahead looked horrendous, with an oversteepened cornicey snow slope blocking passage to the lowpoint. We had both specifically avoided bringing mountaineering boots; the 70 meter rope was fine to carry but the boots were out of the question. So Garrett donned strap-on crampons over Sportiva approach shoes, while I opted for microspikes over my 5.10 Guide Tennies (the hiking boot style).

We both spied a secret mystery chute off to the east – basically heading up the flank of White Top. I’m not saying it’s better than the standard route up Rambaud Pass, but it’s definitely different. The snow was lower angle for a good portion of the mystery chute, but appeared to steepen a bit near the top. My miscrospikes got me to some loose class two terrain, while Garrett continued cramponing his way up the snow. We reasoned the snow could be a bit more pleasant to hike up rather than the chossy class two rock hopping. WRONG!

Now to jog back a bit here, while we were spiking up on the flat rock below the mystery chute, I had said something to the effect of, ‘Hey, you won’t be able to front point in those flimsy approach shoes, so make sure you side step engaging all the points for better traction.’

So about 10 minutes later I look over from the rocks to see Garrett front pointing and slipping and sliding all over the damned snow slope. Unfortunately it had iced up a bit higher in the mystery chute. ‘Dude! What ‘er you doing man?!’

OPERATION AXE RESCUE was thusly engaged. I didn’t even take the time to film a hilarious video (the way a good millenial should) of my partner slipping all over the place. As in ‘The Creation of Adam’ I extended my axe elegantly across the icy divide to where Garrett was able to stretch out and grab it, all the while his ‘pons threatening to rip off completely, himself hanging by a single slippery hold on the edge of the axe. But now, wielding two axes like some kind of Thunder God, he swung his way over to rocky safety, feet dangling below like a couple of slippery dead fish. The might of each axe swing nearly knocked me from my rocky perch.

As it happened this moment turned out be the crux of the whole climb for Garrett. Sadly both of his ‘pons had slid down the slope and we only ever managed to find one of them. I nobly veered slightly off route on the return journey in search of the missing spikes. We reasoned it fell into one of the melted out suncups, you know the really deep kind where there’s a rock at the bottom melting its way to morainal oblivion?

We recovered splendidly and soon found ourselves traversing the cracked slabs of White Top en route to the northwest arete. Much thanks to Bob Burd for the pictorial beta regarding the path of this traverse. By this time it was me who was doing the reeling – the arete is quite terrifying even to the seasoned alpinist. With early ascentists such as Charles Michael, Jules Eichorn, Helen LeConte, Glen Dawson, and of course, Norman Clyde, it is no surprise the Crags are capable of rebuffing all climbers not noble of spirit, and versed in the ethics of backcountry scrambling on loose holds.

In its essence, the climbing on the arete was most reminiscent of Palisades scrambling. For a second I swore I had returned to the Venusian Blind Arete. The lichen even flew the same colors. Of course the rock is ancient – from the times the Sierra had eroded to low hills – but still granitic in character and composed of jagged angular holds. Few jamcracks to be found here, lost in time high on the arete.

After a few of the fourth class steps my mental armour to exposure had reached its theoretical vanishing point. I felt like Alex Honnold on Thank God Ledge. (The comparison is entirely justified……and don’t you try to tell me otherwise!) And so I asked Garrett for a quick belay. He proceeded to scramble up a 25 foot step and called back, ‘It’s easy Jeff, just go for it!’ ‘But I wanted a belay!’

A good partner knows when to push, and when to give. And in this case, it was the right call to push me in that moment. I was perfectly capable of making the moves. Sometimes you just get scared.

We worked our way up a few more notches and steps, and finally I determined to whip out the rope. I had carried it all this way and probably had developed a bias for actually getting some use out of it. And the fear had gone and come back, gone and then returned again. Such are the emotions when you’re rollercoastering up and down a knife edge 2,000 feet above solid ground. Garrett acquiesced and we doubled the rope over for additional protections against abrasions, and to keep us in closer communicative contact. As the climber least likely to fall, I followed along and allowed Garrett to lead the way. It was nice being a bit closer as I could call out and receive some assurance from my partner that he felt good, comfortable with the moves, and to get some back and forth going regarding the routefinding. I’ve noticed that for whatever reason the follower can often notice little deviations along scrambling terrain which help keep the leader on the best line.

The importance of putting time in on the lower roadside crags, and the resulting increased trust and confidence in your partner gained by way of such practice, cannot be overstated. We had in fact simuled (in much the same fashion that we now did) on top of the Crystal Crag by Mammoth Lakes just a few weeks earlier. That had been a great day. Soon we reached a flow state. What many climbers consider the crux downclimb off the knifeblade onto the exposed slab, went free for both of us. No hand line or ludicrous 10 foot rappel required. I had become 100% attuned to my surroundings, allowing the holds to dictate my movements. There wasn’t much gear to be had, but no matter, you’re not supposed to fall up here anyway and Garrett was doing a nice job of draping the rope back and forth between the pinnacles.

Beyond the crux downclimb into the notch, the rock quality and movements along the ridge top reached the next level. In some of the more trying moments on the climb, I had started to sing ‘Crimson and Clover’ as I had seen it set to video footage of Steph Davis soloing on The Diamond. If she could be solid up there, surely I could keep it together on some loose scrambling terrain. Now I began to hum the tune out of joy, on the verge of tears, so happy to pierce the bright afternoon sun sky and the Palisades shining in the distance. Before I knew it Garrett’s voice rang out: he was standing on the summit.

‘YYAAAWWOOOEEEEEE!!!!’

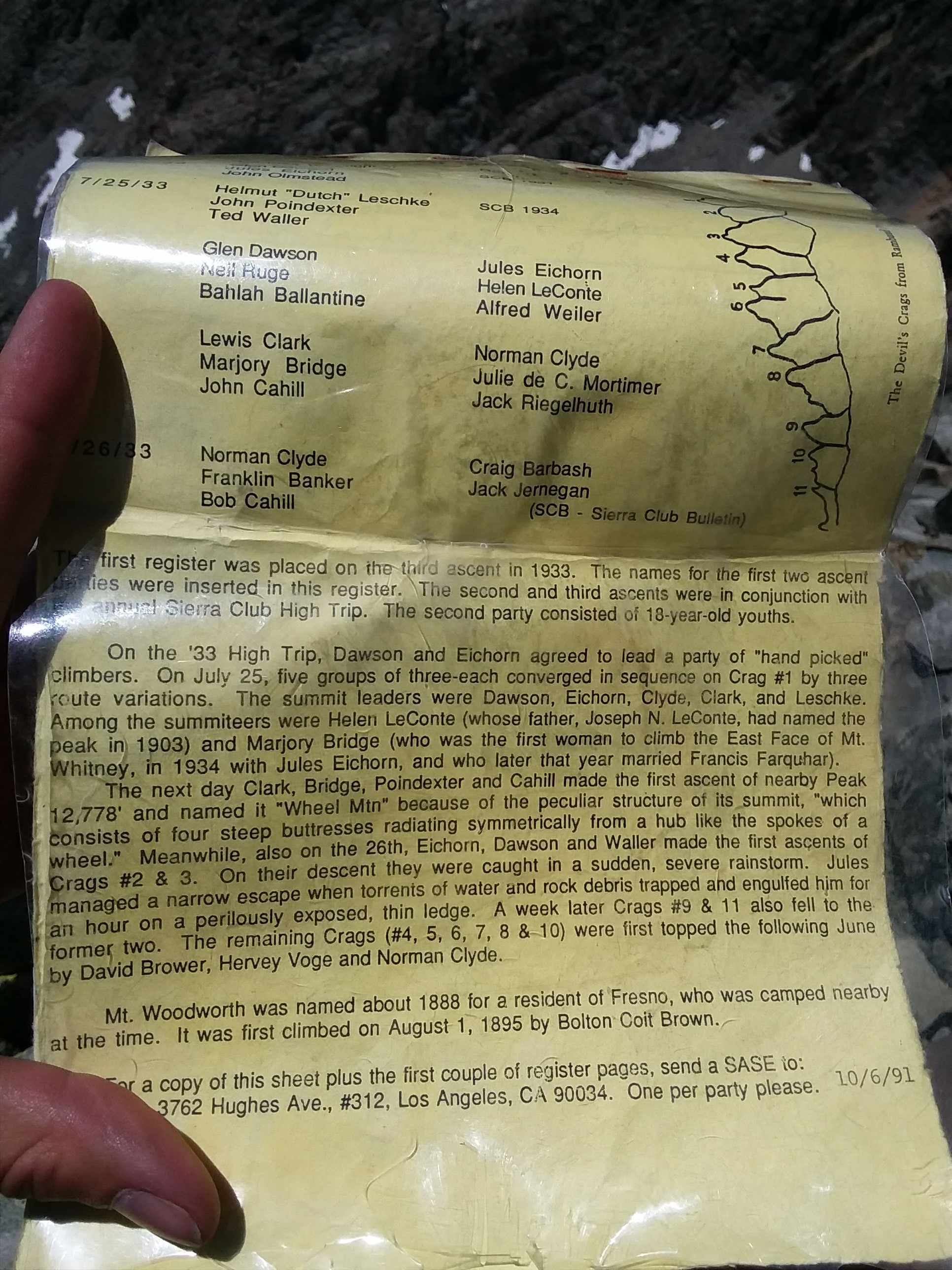

It was a lot of fun perusing the register. A photocopy of the original was in place. Of course all the usual suspects were in there – friends and friends of friends, RJ (my simultaneous guidebook hero and bitter nemesis, both for his characteristic terseness) and Dougle Mantle 7x. Not a single party had visited the peak in 2017. We signed in and began the long second half of the climb.

Everything continued flowing together, as we had dialed all the cruxy moves on the way over. It was a simple matter of slapping some of the more dubious flakes but the body seemed to know just which ones were good and which way to face and balance in the reverse direction; no matter to be adrift in a sea of rock when the foam lapping in every wave is brought into perfect clear focus. We rapped once with the 70 and decided that was enough.

‘You good downclimbing this?’

‘Yeah, it’s better than pulling a mile of rope!’

The further we climbed back along the ridge the more my mind was put at ease, at peace. Soon we were up and over White Top, back to the big pack, which had a lot less water than we had remembered leaving in it.

‘We gotta bag Wheel, it’s on the list!’

‘I’m sick of that stupid SPS list!’ It’s totally arbitrary!’

‘You really want to come back here to get the peak? It’s so close…’

‘UGH! Let’s get it over with…’

And we were off, sans water to Wheel Mountain. Garrett was reduced to stuffing his face with handfuls of snow.

‘I’m pretty sure that’s supposed to make you more dehydrated, ya know.’

‘Yeah but it’s cold and tastes good.’

‘Mmmm, yeah that is a good point. Let me try some of that.’

The slog dragged ever onward but there was a lot of daylight left, so what else were a couple of peakbaggers to do…

As always the SPS had delivered – wherever there is a lack of climbing almost always there’s at least a view to go with it. We were now out and about at that most glorious time of day, high above all the peaks when the long shadows fly across the valleys and drape the peaks in loving embrace.

‘I’m tired, let’s go down.’

‘OK nice work. That 200’ uphill above the pass to reach our secret chute is going to be brutal.’

‘I don’t want to think about it!’

The rest of the day is a bit of a blur, possibly due to the aforementioned dehydration, but also probably because it hadn’t quite sunk in what we had done. I’d give anything for a time machine to run into Charles Michael up there by himself way back in 1913! Standing on the shoulders of giants!

It must have turned into a Type II day at some point. Back at camp the mosquitoes had gone full horde and I didn’t care. No dinner, too much work. I flopped into the tent, rubbed the mask of dead bugs off my face and passed out.

The next day brought brilliant morning alpenglow on the Crags and the prospect of a very long journey back to South Lake. I gazed disdainfully at the rope. Needless to say we were both a bit slow to pack our things. My fuel for the day would be an entire summer sausage conveniently holstered in the side water bottle pouch on my pack.

We both reminisced in sweet LeConte Canyon, Garrett of his time walking the JMT when he had probably first fell in love with The Snowy Range, myself of that time when Craig, Eric and I descended the canyon after a deep climb of Scylla and Charybdis. The logic had been it would be easier to hitchhike back to our car at Lake Sabrina, rather than climb a snowy Echo Col a second time.

Conversation slowed to a standstill as we had reached a nonverbal agreement that breaks would no longer be necessary – it was pedal to the metal back to the Pass. Less thinking == more numbness and less pain. It was all over soon enough. Like always time seemed to speed ahead the closer we came to the trailhead. I’ve noticed that even after a mere long weekend in the backcountry it seems like you’ve been gone an eternity. Then at work on Monday morning the e-mails fly in 10 at a time and the mind careens from total serenity to reckless damage control. I never get much done on Mondays anyway.

By the time we hit the trailhead, I couldn’t hardly feel my feet. My toenails were falling off. Hips, bruised from carrying the big pack. Arms, riddled with mosquito bites. Face, burnt. Legs, like dead weight. But of course these small inconveniences, the bumps bruises scrapes and burns, will fade in time – but one thing will remain………

namely that lonely stretch of ridgeline high in the mountains where for a few moments we were totally and irredeemably free.